The Performance Trap of Migrating Away from Bitnami MongoDB

For years, Bitnami served as the de facto standard for deployments, offering a level of consistency, security and integration that official upstream images usually often failed to match. They bridged the operational gap between raw software binaries and production-ready artifacts, becoming the default choice for DevOps engineers everywhere.

You might have heard that Bitnami announced they're discontinuing their public Docker images. It seemed like the right time to make the move we had been considering anyway, switching to the official MongoDB image. Sounds straightforward, right?

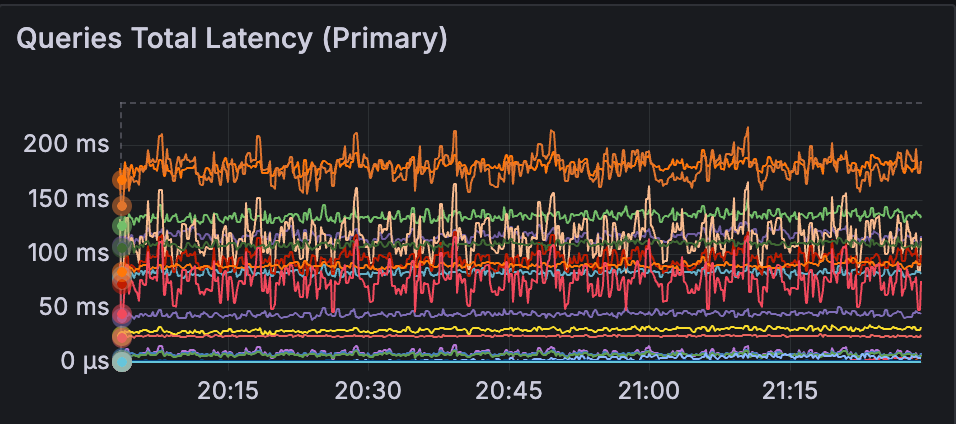

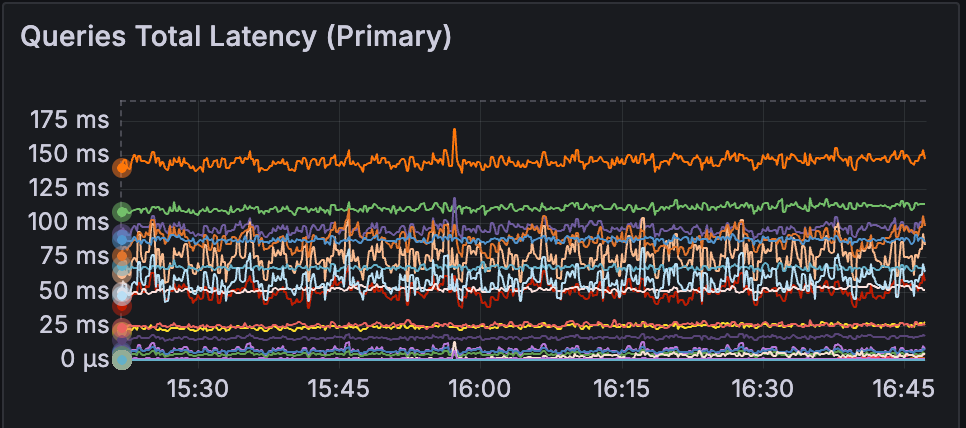

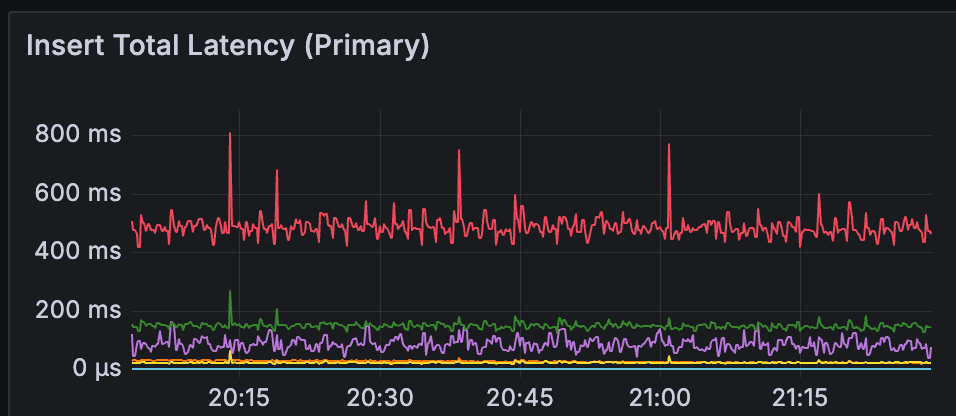

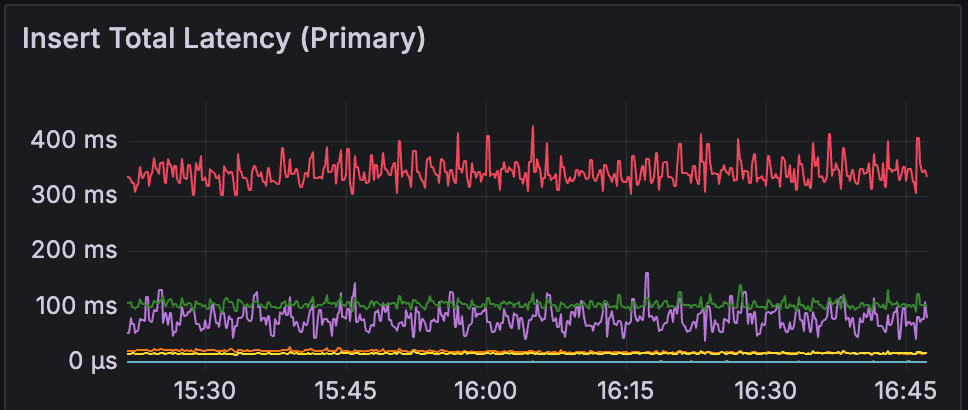

The Performance Degradation

Everything looked promising at first. The migration was easy, requiring just some minor replicaset adjustments. After fixing this up, we ran our performance tests to validate the new setup. Then we saw the numbers.

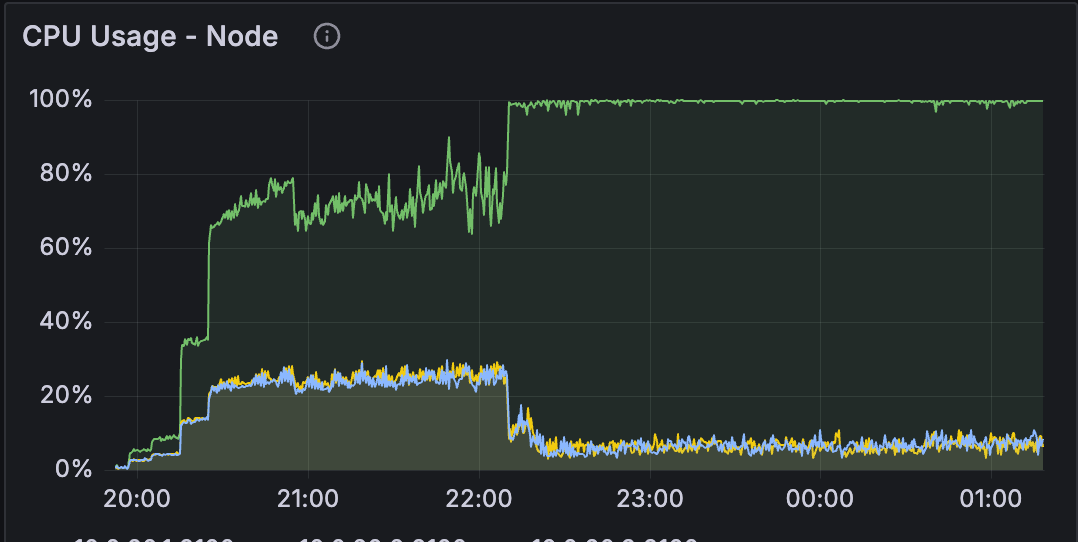

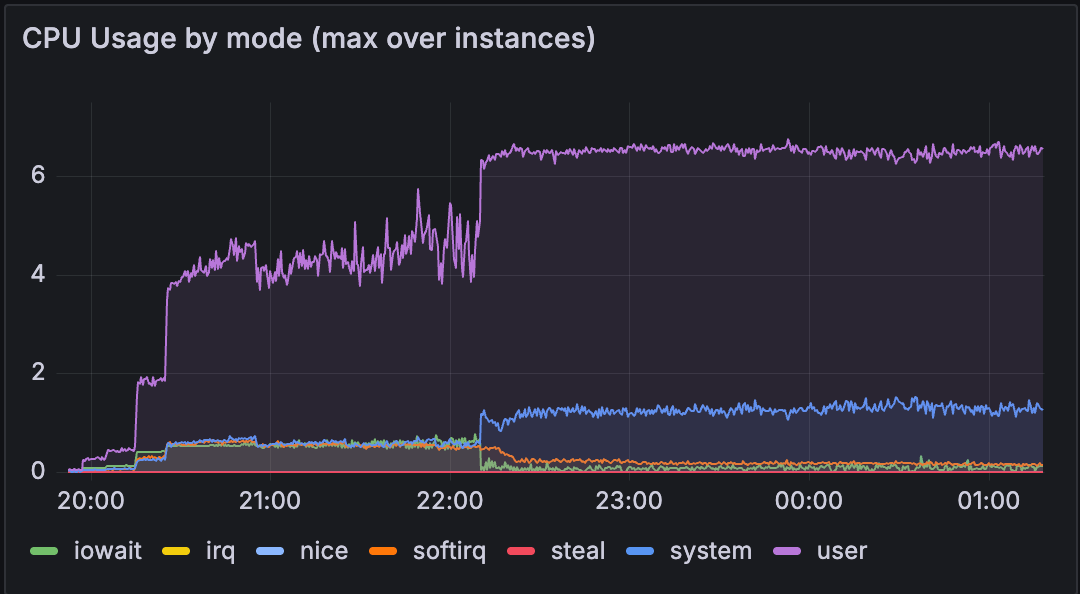

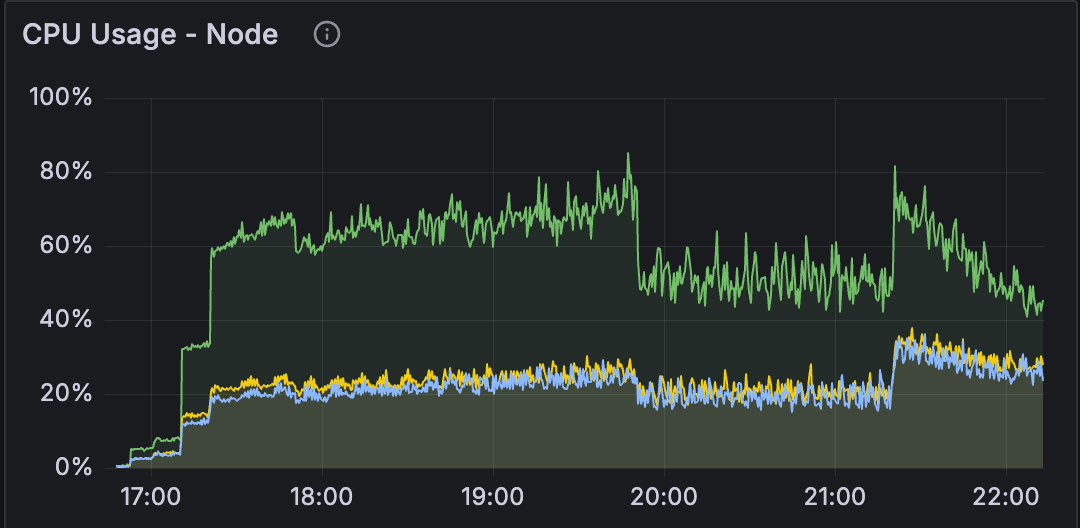

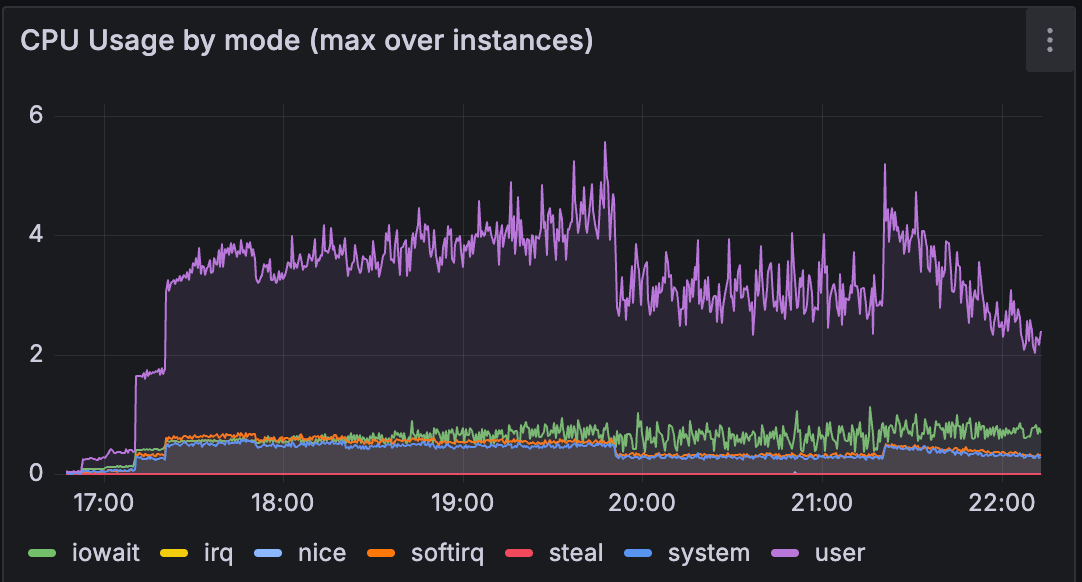

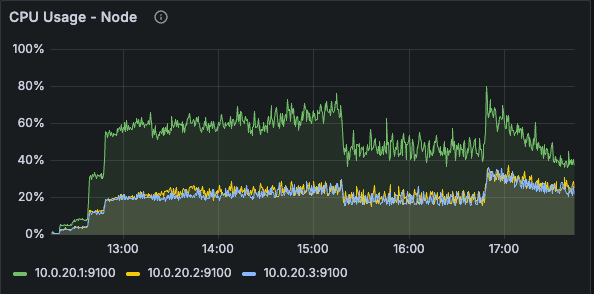

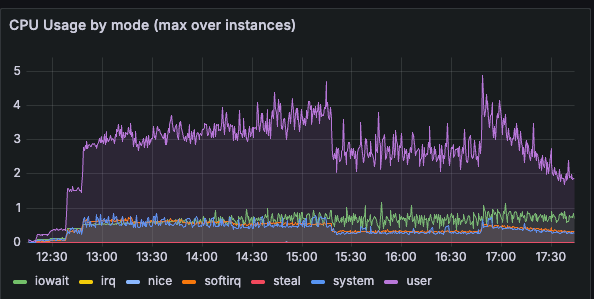

What we found was surprising. The official MongoDB image was performing dramatically worse than Bitnami. We're talking about a significant rise in CPU usage on the same workload and infrastructure, that was completely at odds with our expectations. On paper, everything should have stayed at the same level or even improved slightly.

We didn't expect such a difference in a simple Docker image swap. So it became quite interesting to dig deeper into what was happening.

Following the Dockerfile Breadcrumbs

The first clue came from the Dockerfiles. When we compared the official MongoDB image with Bitnami's, we noticed something curious: the official image was explicitly setting an environment variable that Bitnami didn't use at all:

ENV GLIBC_TUNABLES glibc.pthread.rseq=0

At first glance, this seemed like a random configuration knob. However, after some research it became clear that this is where the different behavior was coming from.

Understanding the use of CPU Caches

To have better overview, we needed to understand how MongoDB handles memory allocation. Starting with version 8.0, MongoDB upgraded its memory allocator, TCMalloc (Google's customized implementation of C's malloc()), to use a new caching strategy. The old approach used per-thread caches: each database thread maintained its own memory cache. This approach was simple but had drawbacks. Under high load with many threads, memory fragmentation could become severe, leading to performance degradation. That's why it was recommended to disable the Transparent Huge Pages (THP) feature on Linux systems running MongoDB in versions < 8.0.

The new approach uses per-CPU caches instead. Rather than each thread managing its own cache, the system allocates cache memory to each CPU core. This is fundamentally more efficient for modern multi-core systems because:

- Memory fragmentation decreases significantly

- Cache efficiency improves with better locality

- The system becomes more resilient under high-stress workloads

But there's a catch. This new per-CPU caching relies on a kernel feature called restartable sequences (rseq). Think of rseq as a way for TCMalloc to atomically claim a piece of memory from a CPU-specific cache without needing expensive locks.

The problem: if another system library has already registered an rseq structure in the process, TCMalloc can't use rseq. And guess what? The glibc library (the C standard library that runs on every Linux system) was registering rseq before TCMalloc got a chance.

This is why the official MongoDB image sets GLIBC_TUNABLES='glibc.pthread.rseq=0'. It's telling glibc: "Don't use rseq, let TCMalloc have it."

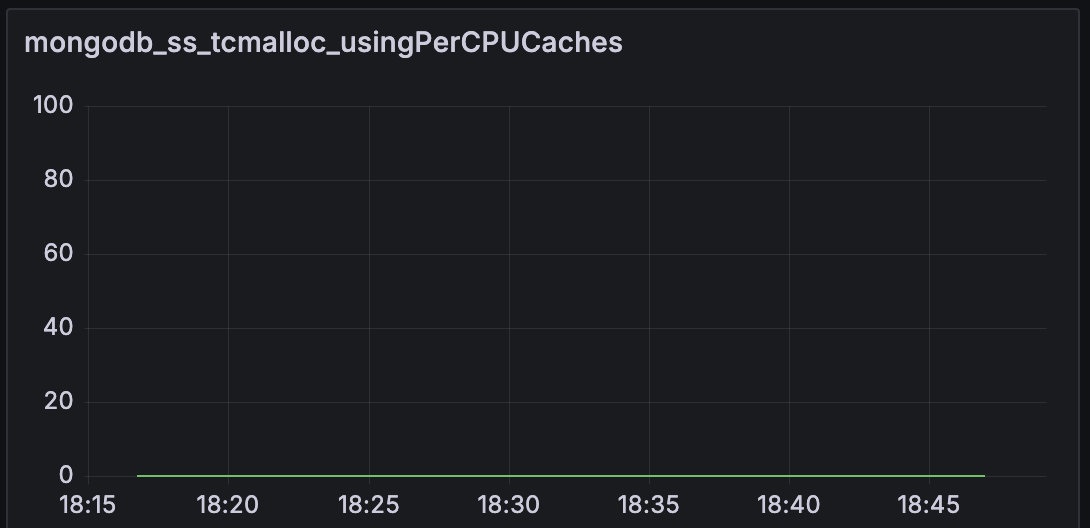

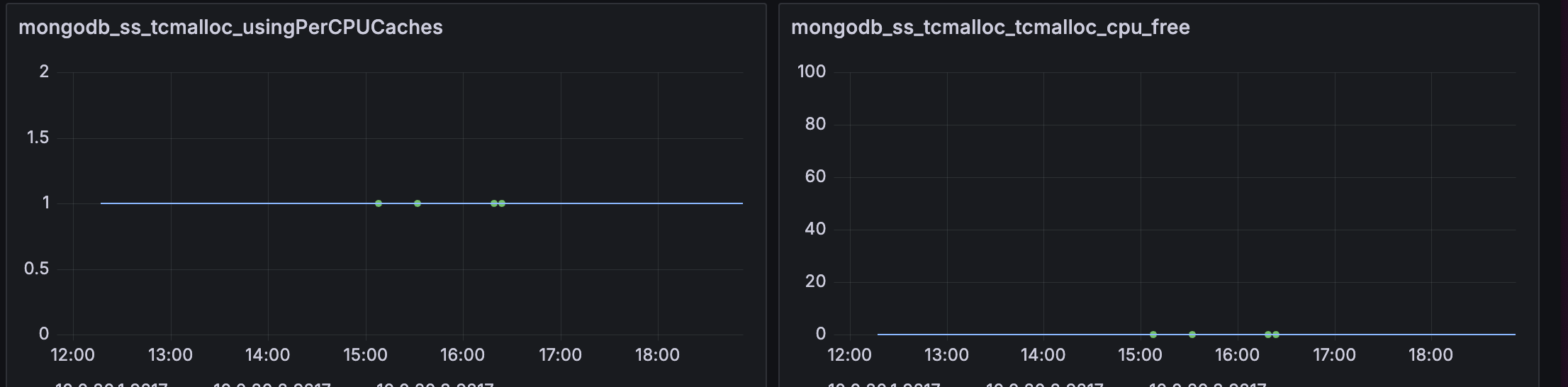

To gain insight into which caching strategy is in use, MongoDB exposes the tcmalloc.usingPerCpuCaches metric.

Leveling the Playing Field

To ensure that the use of per-CPU cache caused the problems we observed, we ran the official MongoDB image but enabled rseq in glibc instead:

GLIBC_TUNABLES=glibc.pthread.rseq=1

The result? MongoDB fell back to per-thread caching, just like it was in Bitnami. And just like the old days, the CPU usage came back to the same level as in the Bitnami image.

We were making progress, but this felt like we were solving the wrong problem. The official image was intentionally trying to use per-CPU caches. That's clearly the recommended approach. So why wasn't it working as advertised?

The Configuration Caveat

We enabled per-CPU caching properly, yet something odd happened: the metrics showed that per-CPU caches were enabled (tcmalloc.usingPerCpuCaches = true), but the actual cache wasn't being used. We could see this in the tcmalloc.cpu_free metric, which sat stubbornly at zero, a value that contradicts the expected behavior for an active cache.

We dug into MongoDB's documentation, TCMalloc's documentation and tried different THP and defragmentation configurations. Nothing really worked. The answer was found buried in a Jira issue: TCMalloc needs to know how much memory it can allocate to per-CPU caches. Without explicit configuration, it can't safely reserve CPU-specific cache buffers.

MongoDB tries to infer this in two ways:

- Check if the Docker container has a memory limit set

- Use the

MONGO_TCMALLOC_PER_CPU_CACHE_SIZE_BYTESenvironment variable

We are running our performance tests in a containerized environment without explicit memory limits, and we hadn't set the configuration variable. TCMalloc saw an uncertain situation and defaulted to conservatively not allocating any per-CPU cache space. You can read more about this in SERVER-109273.

The Final Piece

Once we set the environment variable on our MongoDB containers:

MONGO_TCMALLOC_PER_CPU_CACHE_SIZE_BYTES=10485760

Everything changed. The tcmalloc.cpu_free metric shot up, indicating that per-CPU caches were now actually allocated and in use. Performance slightly improved beyond our Bitnami (per-thread cache) baseline as promised by the Atlas team.

What We Learned

Always double check the image you use. The Bitnami image didn't have per-CPU caching enabled at all, so it never had this problem. By switching to the official image, we started to use per-CPU caching, but only after understanding and configuring the environment variables that make it possible.

Disclaimer

MongoDB®, Bitnami®, Docker®, and Linux® are trademarks of their respective owners. This article is for informational purposes only and is not affiliated with, sponsored by, or endorsed by these trademark holders. All technical findings are based on independent testing.